SINGING GAMES AND NURSERY RHYMES

PART 2

“Catching” Games

In these games, two players make an arch while the others pass through in single file while singing a song. The arch is then lowered at the end of the song to “catch” a player. Perhaps the most common example of such a game is “London Bridge is Falling Down.” A similar game is played to the tune of “Oranges and Lemons.”

Early folklorists tended to reflect contemporary theories and beliefs, including the view that singing games were a form of pagan survivalism, which led Alice Gomme to conclude that ‘London Bridge Is Broken Down’ reflected a memory of child sacrifice. The origins are obscure as children over many generations have changed the game.

“London Bridge Is Falling Down” (also known as “My Fair Lady” or simply “London Bridge”) is a traditional nursery rhyme and singing game, which is found in different versions all over the world. It deals with the disrepair of London Bridge and attempts, realistic or fanciful, to repair it. It may date back to bridge rhymes and games of the late Middle Ages, but the earliest records of the rhyme in English are from the seventeenth century. The lyrics were first printed in close to its modern form in the mid-eighteenth century and became popular, particularly in Britain and the United States in the nineteenth century. The modern melody was first recorded in the late nineteenth century and the game resembles arch games of the Middle Ages, but seems to have taken its modern form in the late nineteenth century. Several theories have been advanced to explain the meaning of the rhyme and the identity of the “fair lady” of the refrain. The rhyme is one of the most well known in the world and has been referenced in a variety of literature and popular culture.

There is considerable variation in the lyrics of the rhyme. The most frequently used first verse is:

London Bridge is falling down,

Falling down, falling down.

London Bridge is falling down,

My fair lady.

In the version quoted by Iona and Peter Opie in 1951 the full lyrics were:

London Bridge is broken down,

Broken down, broken down.

London Bridge is broken down,

My fair lady.

Build it up with wood and clay,

Wood and clay, wood and clay,

Build it up with wood and clay,

My fair lady.

Wood and clay will wash away,

Wash away, wash away,

Wood and clay will wash away,

My fair lady.

Build it up with bricks and mortar,

Bricks and mortar, bricks and mortar,

Build it up with bricks and mortar,

My fair lady.

Bricks and mortar will not stay,

Will not stay, will not stay,

Bricks and mortar will not stay,

My fair lady.

Build it up with iron and steel,

Iron and steel, iron and steel,

Build it up with iron and steel,

My fair lady.

Iron and steel will bend and bow, Bend and bow, bend and bow, Iron and steel will bend and bow, My fair lady.

Build it up with silver and gold,

Silver and gold, silver and gold,

Build it up with silver and gold,

My fair lady.

Silver and gold will be stolen away,

Stolen away, stolen away,

Silver and gold will be stolen away,

My fair lady.

Set a man to watch all night,

Watch all night, watch all night,

Set a man to watch all night,

My fair lady.

Suppose the man should fall asleep,

Fall asleep, fall asleep,

Suppose the man should fall asleep?

My fair lady.

Give him a pipe to smoke all night,

Smoke all night, smoke all night,

Give him a pipe to smoke all night,

My fair lady.

In its most common form it relies on a double repetition, rather than a rhyming scheme, which is frequently used in children’s rhymes and stories. The Roud Folk Song Index, which catalogues folk songs and their variations by number, classifies the song as 502.

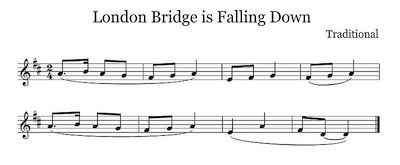

The melody now most associated with the rhyme.

A melody is recorded for “London Bridge” in an edition of John Playford’s The Dancing Master published in 1718, but it differs from the modern tune and no lyrics were given. An issue of Blackwood’s Magazine in 1821 noted the rhyme as a being sung to the tune of “Nancy Dawson”, also known as “Nuts in May” and the same tune was given in Richard Thomson’s Chronicles of London Bridge (1827). Another tune was recorded in Samuel Arnold’s Juvenile Amusements in 1797. E. F. Rimbault’s Nursery Rhymes (1836) has the same first line, but then a different tune. The tune now associated with the rhyme was first recorded in 1879 in the US in A. H. Rosewig’s Illustrated National Songs and Games.

The Game:

The rhyme is often used in a children’s singing game, which exists in a wide variety of forms, with additional verses. Most versions are similar to the actions used in the rhyme “Oranges and Lemons.” The most common is that two players hold hands and make an arch with their arms while the others pass through in single file. The “arch” is then lowered at the song’s end to “catch” a player. In the United States it is common for two teams of those that have been caught to engage in a tug of war. In England until the nineteenth century the song may have been accompanied by a circle dance, but arch games are known to have been common across late medieval Europe. Five of nine versions published by Alice Gomme in 1894 included references to a prisoner who has stolen a watch and chain. This may be a late nineteenth century addition from another game called “Hark the Robbers”, or “Watch and Chain”. This rhyme is sung to the same tune and may be an offshoot of “London Bridge” or the remnant of a distinct game. In one version the first two verses have the lyrics:

Who has stole my watch and chain,

Watch and chain, watch and chain;

Who has stole my watch and chain,

My fair lady?

Off to prison you must go,

You must go, you must go;

Off to prison you must go,

My fair lady.

Origins:

Detail from Philippe Pigouchet’s Heures a lusaige de Paris (1497), showing an arch game similar to that known to be associated with the above rhyme.

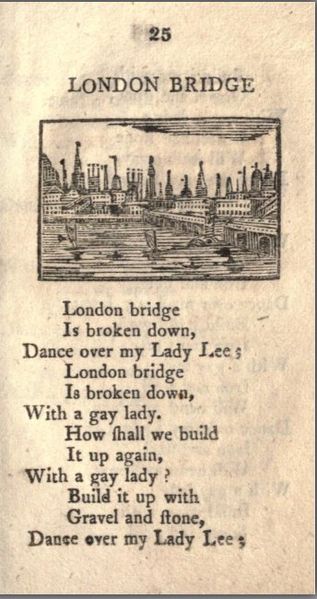

The earliest printed English version is in the oldest extant collection of nursery rhymes, Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song Book, printed by John Newbery in London (c. 1744), with the following text:

Above is first page of the rhyme from 1815 edition of Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song Book (c. 1744).

Oranges and Lemons

“Oranges and Lemons” is an English nursery rhyme and singing game which refers to the bells of several churches, all within or close to the City of London. It is listed in the Roud Folk Song Index as #13190.

Lyrics

Oranges and lemons,

Say the bells of St. Clement’s.

You owe me five farthings,

Say the bells of St. Martin’s.

When will you pay me?

Say the bells of Old Bailey.

When I grow rich,

Say the bells of Shoreditch.

When will that be?

Say the bells of Stepney.

I do not know,

Says the great bell of Bow.

Here comes a candle to light you to bed,

And here comes a chopper to chop off your head!

As a game:

The song is used in a children’s singing game with the same name, in which the players file, in pairs, through an arch made by two of the players (made by having the players face each other, raise their arms over their head, and clasp their partners’ hands). The challenge comes during the final lines:

• Here comes a candle to light you to bed.

• Here comes a chopper to chop off your head.

• (Chip chop, chip chop, the last man’s dead.)

On the last word, the children forming the arch drop their arms to catch the pair of children currently passing through, who are then “out” and must form another arch next to the existing one. In this way, the series of arches becomes a steadily lengthening tunnel through which each set of two players have to run faster and faster to escape in time.

Alternative versions of the game include: children caught “out” by the last rhyme may stand behind one of the children forming the original arch, instead of forming additional arches; and, children forming “arches” may bring their hands down for each word of the last line, while the children passing through the arches run as fast as they can to avoid being caught on the last word. It was often the case, in Scottish playgrounds, that children would pair into boy and girl and the ones “caught” would have to kiss.

Below is an earlier version of the rhyme, which is included in Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song Book (c. 1744):

Two Sticks and Apple,

Ring ye Bells at Whitechapple,

Old Father Bald Pate,

Ring ye Bells Aldgate,

Maids in White Aprons,

Ring ye Bells a St. Catherines,

Oranges and Lemons,

Ring ye bells at St. Clements,

When will you pay me,

Ring ye Bells at ye Old Bailey,

When I am Rich,

Ring ye Bells at Fleetditch,

When will that be,

Ring ye Bells at Stepney,

When I am Old,

Ring ye Bells at Pauls.

There is considerable variation in the churches and lines attached to them in versions printed in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, which makes any overall meaning difficult to establish. The final two lines of the modern version were first collected by James Orchard Halliwell in the 1840s.

Oranges and Lemons was the name of a square-four-eight-dance, published in Playford’s, Dancing Master in 1665, but it is not clear if this relates to this rhyme. Similar rhymes naming churches and giving rhymes to their names can be found in other parts of England, including Shropshire and Derby, where they were sung on festival days, on which bells would also have been rung.

The identity of the churches is not always clear, but the following have been suggested, along with some factors that may have influenced the accompanying statements:

St. Martin’s may be St Martin Orgar or St. Martin’s Lane in the city, where money lenders used to live. St Sepulchre-without-Newgate (opposite the Old Bailey) is near the Fleet Prison where debtors were held. St Leonard’s, Shoreditch is just outside the old city walls. St Dunstan’s, Stepney is also outside the city walls. Bow is St Mary-le-Bow in Cheapside. St. Helen’s, in the longer version of the song, is St Helen’s Bishopsgate, in the city. St. Clements’s may be St Clement Danes or St Clement Eastcheap both of which are near the wharves where merchantmen landed citrus fruits.

The tune is reminiscent of change ringing, and the intonation of each line is said to correspond with the distinct sounds of each church’s bells. Today, the bells of St Clement Danes ring out the tune of the rhyme.

RESOURCES AND FURTHER READING:

Baring-Gould, William S. and Ceil. The Annotated Mother Goose: Nursery Rhymes Old and New, Arranged and Explained. New York: Bramhall House, 1958.

Brewster, Paul G. Children’s Games and Rhymes. New York: Ayer Co Pub.1976.

Campbell, Andrea. Great Games for Great Parties: How to Throw a Perfect Party.

New York: Sterling, 1991.

Cooper, Mary. Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song Book, London: printed by John Newbery, c. 1744.

Denslow, W.W. Mother Goose, New York: Dodo Press, 1901.

Halliwell, James Orchard. The Nursery Rhymes of England, Oxford: University Press. 1846.

Herman, D. The Cambridge Companion to Narrative. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2007.

James, Arlene. A Family to Share. Waterville, Me.: Thorndike Press, 2006.

Lomax, Alan. Folk Songs of North America. Garden City, N.J.: Doubleday, 1960.

Miller, Olive Beaupré. In the Nursery of My Bookhouse. Chicago: The Bookhouse for Children Publishers (1920).

Opie, I.; Opie, P. (1951). The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes (1997 ed.). Oxford: University Press. pp. 349–50.

Rizzo, C. All the Ways Home: Parenting and Children. Norwich VT: New Victoria Publishers. p. 104. 1995.

Roud, S. The Lore of the Playground: One Hundred Years of Children’s Games, Rhymes & Traditions (New York City, NY: Random House, 2010

Wentworth, George. Smith, David Eugene. Work and Play with Numbers. Boston: Ginn & Company.1912.

Whitmore, William H. The Original Mother Goose’s Melody, as First Issued by John Newbery, of London, About A.D., 1760. Albany: Joel Munsell’s Sons, 1889.

Wollaston, Mary A. (compiler). The Song Play Book: Singing Games for Children. New York: A.S. Barnes and Company (1922).